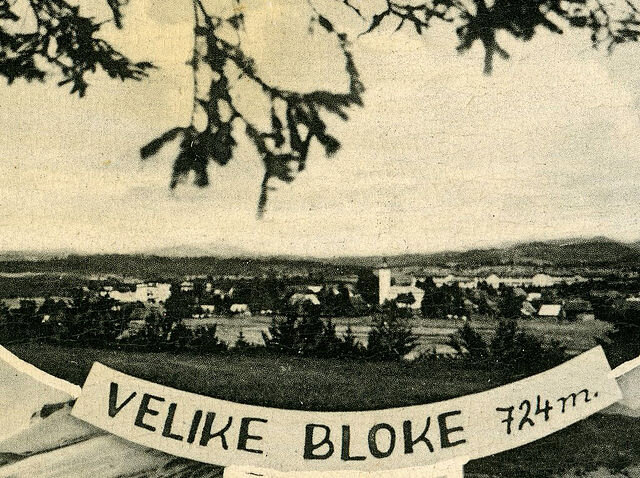

33: Bloke // Six Months of Winter, Six Months of Cold

The beautiful wilderness of Bloke, Slovenia // © Kristjan V / shutterstock

‘Welcome to Bloke, where for six months of the year it is cold, and for six months of the year it is winter’

It isn’t often that the first thing said to you in a town leaves a genuine long-lasting impression. Those travellers with predetermined ideas about the world’s classic cities may be lucky enough to tick this box; Francophones will recall the sweet words that they hear upon arrival in Paris, those enamoured with the idea of London will joyfully recollect their first conversations in the Big Smoke, and the men and women who waited their lives to visit New York will retain those first moments forever. Those are three of the most visited cities on the planet, with more than 106 million people visiting them per year. Bloke has been an independent municipality since 1998, and one with less than two thousand inhabitants at that. Most Slovenes will never make the trip to the town whose name comes from nearby flood meadows.

And in truth, why would they? Bloke is well and truly in the wilderness. There was nothing, anywhere, nowhere. This isn’t entirely a factual claim of course, as those less than two thousand need to live somewhere. There are buildings, there is even a ranch and a museum dedicated to skis. Wilderness isn’t always about physical absence, and Bloke was my introduction to the psychological wilderness that many fear. I was there, I was going to be there for the rest of the day, and the hefty gentleman whose delight at his admittedly clever wisecrack was going to be my source of sanity or lack thereof for at least the next 24 hours. I have read many travel books in my relatively short time on this mortal coil, and almost all of them would follow this introduction by stating that they were internally excited - I was shitting myself.

Small towns often encourage large amounts of pride, as those destined to inhabit them search for ways to breathe life into their world. Alcohol often works in a similar way, and the combination of excessive alcohol and relatively uninhabited surroundings can sometimes lead to exclamations of ‘there’s nowhere on earth like it’, ‘this is the true heart of the country’ and ‘I never want to leave’. I was too busy trying to conjure up an escape plan in those first moments to consider it, but less than one rotation around the sun later I found myself saying all three of those sentences, or at least slurring them. The ideas wouldn’t last forever, but I had found my own personal spot in Slovenia. To this day, I’ve not met another individual who claims Bloke to be their favourite part of the country. Well, no other individual other than those that live there of course.

Getting to Bloke is no easy task. I was relatively lucky in that a bus took to me to Postojna, where a friend intercepted and took me up into the mountains via car, but this didn’t exactly lessen the nerves that come with being dropped off the middle of jack-crack nowhere. If the bus wasn’t going to go there, how the heck was I going to get away? Just moments after I had arrived, failed to take stock of my surroundings and been treated to a little bit of Bloke humour, the first of many schnapps was slammed into my particularly apprehensive hand. What followed were almost 800 years of history and more information about skiing than I could possibly remember. Bloke is the home of skiing, if you weren’t aware.

‘Bloke is the home of skiing you know’, insisted the man with the walrus moustache as he poured another schnapps into my glass with the subtlety of, well, a large man in a Slovenian mountain village drinking schnapps. Of course, that isn’t entirely true. The people of Bloke are thought to have been the first in Central Europe to use skis to get around on snow, a claim with far too many qualifiers to truly matter. Was I going to try to argue with the moustache mountain? Absolutely not.

It was Janez Vajkard Valvasor, a man whose story is too important to bring up in such a throwaway manner so early in this book, who first brought light to the inventions of the people of Bloke, talking about people here sliding down the snowy hills into the valley at incredible speed. They were able to do so thanks to two wooden planks, a quarter of an inch thick, half a foot wide and five feet long, which were strapped to their feet by a leather strap. A wooden stick helped guide what Valvasor presumed were farmers down the hill, and thus the Bloke skiing dynasty began. I knew all of this because we had now moved into the Bloke Skiing Museum, and my leader (there was no doubt who was controlling the pace of this trip) was escorting me around the artefacts and information boards inside. The museum itself is a fairly recent creation, housing a history so important to Bloke that the municipality flag features a man on skis. I was almost beginning to feel comfortable in this environment. It may have been the history, the schnapps, or a virulent combination of the two, but my increased confidence was beginning to blend well with the forthright intensity of the man I had by now (privately) named Captain Bloke.

‘You must try on the Bloke skis, you must become a Bloke skier, it is absolutely imperative’. And thus the confidence vanished. What? Try on skis?! Then what? Ski? Despite living in Slovenia I had never been skiing, managing to successfully withstand the constant cries of ‘Oh you really should go’, ‘It is a lot of fun’ and ‘it is cheap and we pretty much just drink all day’. Was Captain Bloke really going to force me to try on a pair of skis for the first time when I was four schnapps deep into what for all the world was going to be a long day of schnapps? Yes. Yes, he was.

When I was a young boy coming to the end of my single-digit years in lieu of doubling them up, I was a gymnast. I wasn’t a particularly good one, but I was the only boy in my school year who took part in gymnastics with anything approaching confidence. It was the years watching professional wrestling that made the difference, a desire to fly around like Super Calo or Juventud Guerrera. I had good balance too, becoming somewhat notorious in gymnastics lessons for an admittedly excessively long headstand.

I wasn’t a child anymore though. I was a man-child, an intimidated, drunk man-child. Every fibre of my being was screaming ‘no’, but Captain Bloke clearly wasn’t going to take that for an answer. ‘Who comes to Bloke and doesn’t try on ski? Only idiots and babies’. He had a point, although I’d put money on the latter having tried it and a bout of early 20s neurosis meant I had little problem referring to myself as the former. The decision was out of my hands, and I clumsily agreed to put on the Bloke skis, a couple of wooden planks that seemed to contain more damp than hope. I had visions of slipping and sliding in the empty Bloke landscape, of Captain Bloke laughing as I fell head over foot in front of the unimpressed horses at the ranch. Captain Bloke was clearly going to ask me to ride a horse as well, so I hastily surmised that skis were the safer option.

Captain Bloke strapped the two damp-ridden wooden planks to my feet and any vague confidence that I had been able to muster whilst he was quickly evaporated. There was no way I was going to be able to ski in these things. There probably wasn’t any way that I was going to be able to ski full stop, but the potential shame was too strong. I had no choice. Captain Bloke didn’t help matters, making me stand and wait as he located a little fez-style hat, made out of the skin of far too many dormice, although in my inebriated and terrified state I had convinced myself that the plural was actually ‘dormouses’.

‘Okay, let me take a picture of you, you look ridiculous. Then we go back to the inn’. Hold on, what? You mean I’m not actually going outside to ski? Did I put myself through all of that simply for a photograph opportunity? ‘You thought you were going to ski? Don’t be silly, you would fall over and break your leg. The museum isn’t insured for such things, and you obviously have no skill’. Captain Bloke had a point. He had two points, to be correct. I had dodged a bullet, albeit a bullet that was entirely imaginary.